A Faculty of Medicine neuroscientist has identified a common ancestral gene that enabled the evolution of advanced life over a billion years ago.

The gene, found in all complex organisms, including plants and animals, encodes for a large group of enzymes known as protein kinases that enabled cells to be larger and to rapidly transfer information from one part to another.

“If the duplications and subsequent mutations of this gene during evolution didn’t happen, then life would be completely different today,” says Steven Pelech, a Professor in Division of Neurology. “The most advanced life on our planet would probably still be bacterial slime.”

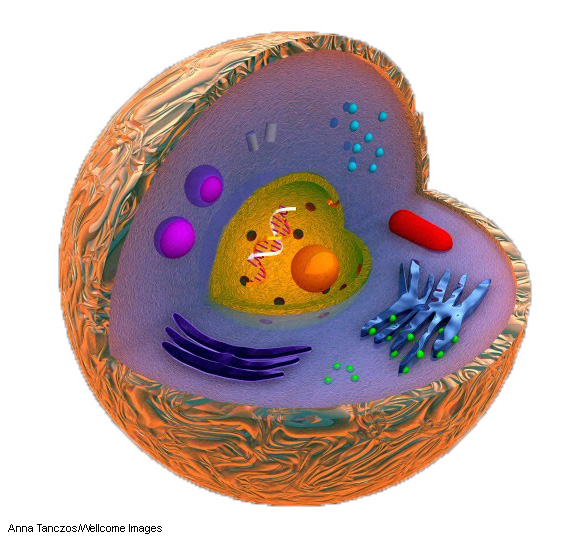

Plants, animals, mushrooms and more all exist because they are made up of eukaryotic cells that are larger and far more complex than bacteria. Inside of these eukaryotic cells are hundreds of organelles that perform diverse functions to keep them living, just as different organs do for the human body.

The new research, published this week in the Journal of Biological Chemistry, identifies the gene that gave rise to protein kinases. On a cellular scale, these highly interactive signaling proteins play a role similar to the neurons in the brain by transferring information throughout the cell by a process known as protein phosphorylation.

This ability to transmit signals from one part of the cell to another not only enabled cells to become more complex internally, but also allowed cells to come together to form systems, paving the way for the evolution of intelligent life.

Research into these enzymes has become very important to medicine. More than 400 human diseases like cancer and diabetes are linked to problems with cell signaling. Disease occurs when a cell gets misinformed or confused. Today about one-third of all pharmaceutical drug development is targeted at protein kinases.

For more than 30 years, researchers have known that most protein kinases came from a common ancestor because their genes are so similar.

“From sequencing the genomes of humans, we knew that about 500 genes for different protein kinases all had similar blueprints,” said Dr. Pelech, a founding scientist of the Biomedical Research Centre, and an investigator with the Vancouver Coastal Health Research Institute. “Our new research revealed that the gene probably originated from bacteria for facilitating the synthesis of proteins and then mutated to acquire completely new functions.”

The same gene that gave rise to protein kinases also led to the formation of a group of enzymes know as choline and ethanolamine kinases. The choline kinase enzyme is critical for the production of phosphatidylcholine, a major component of the membranes that wrap around eukaryotic cells and their organelles, but is missing from bacteria.

Dr. Pelech says that the approach they used to study the evolution of this gene could be adapted to study other important protein families and could eventually lead to the creation of a protein version of the evolutionary tree of life.