How UBC put James Card on the road north, to a town that desperately needed him

A decade ago, Mackenzie – a mill town nestled in the Rocky Mountain Trench at the southern end of Williston Lake – seemed to have its health care needs well in hand, with four physicians tending patients at the hospital and health centre. And then, in the words of Barbara Crook, the district’s health services administrator, “it all seemed to melt away.”

One by one, the doctors – all transplants from South Africa – packed up and left. A husband-and-wife team returned to their homeland; the other two, perhaps feeling overburdened by the resulting workload, left for Alberta.

Crook scrambled to fill the gaps with physicians on the locum circuit. The best she could usually manage was getting a physician to stay for a year. Patients became accustomed to being treated by a new doctor each time they visited, eliminating much hope for continuity of care. At one point, the 24-hour emergency room had to shut down for two days. Supervisors at the town’s mills knew that if one of their employees had a serious injury, the ambulance would bypass the hospital and head straight down Highway 97 to Prince George, a two-hour drive south.

It was a situation that had been playing out, again and again, in the small towns of northern British Columbia – the very situation that had prompted residents and civic leaders to stage a health care rally in Prince George in 2000, demanding that provincial leaders do something about the region’s chronic physician shortage.

Then help arrived, in the person of a quiet, young man named James Card.

And then it kept on coming.

Planting the seed

He grew up in Maple Ridge, but felt more at home in B.C.’s rugged back country than he did in the suburbs of the Lower Mainland. Becoming a doctor wasn’t in his plan, even after graduating from university.

Instead, he took a job planting trees in the north. And it was during one of those outings, not too far from Mackenzie, that news came over the radio about the rally in Prince George.

“That’s when the seed started to set,” he recalls. “It was not something I had grown up wanting to do, but I saw the opportunity.”

When the time came to act on his idea, the rally had borne fruit – in 2004, UBC’s medical education program began its expansion beyond the Lower Mainland, taking root in Prince George and Victoria. By distributing doctor training throughout the province, the thinking went, more doctors would be likely to practice medicine throughout the province.

L-R: James Card at the Northern Medical Program graduation, with then Clerkship Director Galt Wilson and then Regional Associate Dean Dave Snadden.

He was accepted into the first class of the Northern Medical Program, created in partnership with the University of Northern British Columbia. He and his classmates experienced the same curriculum as their fellow UBC students in Vancouver and Victoria, with many classes conducted by videoconferencing.

After earning his medical degree in 2008, Dr. Card remained in Prince George for a two-year residency in family medicine – a program established about a decade before the Northern Medical Program. By 2010, he had become one of the first fully-licensed physicians to emerge from UBC’s distributed education program. (Residencies for other specialties typically take five years, so

many of his classmates spent several more years in training.)

Dr. Card stayed in the North, without quite settling down. He pursued a variety of locums (temporary assignments) around the province, filling in for doctors on vacation or maternity leave. He spent most of his time in Prince George, but also did stints in his hometown of Maple Ridge, the bustling maternity ward of Surrey Memorial Hospital, and a small town he knew well from his tree-planting days: Mackenzie.

“For people who like the outdoors, Mackenzie is fantastic,” Dr. Card says. “Incredible lakes, hiking, boating, fishing, skiing. And I enjoyed the type of work.”

When news of an opening there surfaced, he and his wife Jessica agreed that it would be a nice change of scenery during her upcoming maternity leave. He took the job and they bought a house, figuring the investment ($85,000) could be recouped, more or less, if they chose to sell in a year; if not, they could make it a weekend retreat from what they figured would be their workaday existence in Prince George.

No one thought Dr. Card’s arrival in the summer of 2011 heralded a new chapter in Mackenzie’s health care saga. Dr. Card himself, realizing what kind of workload he was assuming, figured this would be another tour of duty – do your time and get out.

“Mackenzie is a community of just under 5,000 residents, plus lots of transient workers, with a 24/7 emergency room, hospital in-patients and long-term care patients,” he says. “Our clinic usually sees over 60 patients a day, with another 15 a day in emergency. To service that with three physicians, you have to be on call every third day, with the potential of being up all night.”

But soon after arriving, Dr. Card started to see this as more than just another assignment, and he began trying to make a difference – because of who he was before becoming a medical student, and who he became during his medical education and residency.

Aggressive lobbying and marketing

His timing, it turns out, was exquisite.

Northern Health had just instituted an “alternate payment plan” in Mackenzie, paying doctors based on how many hours they work, instead of how many patients they see (commonly known as “fee-for-service”).

“It allows you to practice a much better style of medicine,” Dr. Card says. “You’re not trying to run the turnstile to get your dollars up. You can focus on acute issues, and take time if need be.”

At such alternate payment plan sites, the Ministry of Health decides how many doctors’ salaries it’s willing to pay. When Dr. Card arrived, the ministry had allocated three physicians to Mackenzie. The two other positions were filled – tenuously – by yet another South African doctor and a series of locuming doctors.

Dr. Card wrote to Northern Health, laying out the case for a fourth physician. Northern Health agreed.

“If they had refused, I wouldn’t have stayed beyond my year,” Dr. Card says. “When they agreed, that’s when I started to get invested in the place.”

Dr. Card’s next step was filling that new position, and perhaps even the position that was continually being back-filled through locums.

His first victory came easy: a former fellow resident from the Prince George family medicine program who, as chance would have it, shared a name with the town – Colin MacKenzie.

“I was basically bugging him since the day I started working in Mackenzie,” Dr. Card says.

Then Dr. Card shifted into full-blown marketing mode, targeting other residents in Prince George with the zeal of a time-share salesman.

This was something that hadn’t been done before – as a resident, he received brochures advertising physician openings in rural or remote areas of Saskatchewan and Ontario, but nothing closer to home.

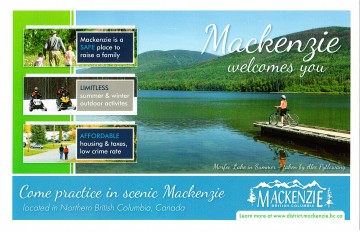

With financial support from Mackenzie, he made postcards extolling the Mackenzie experience, slipping them into the mail slots of residents at University Hospital of Northern B.C.

He gave lunchtime presentations to that target audience, offering free food, to anyone willing to sit through his PowerPoint slides. He attended a rural medicine conference in Whistler (courtesy of Mackenzie), to drum up interest among attendees.

And despite Mackenzie’s eight months of winter and temperatures of 30 below, Dr. Card thought he had something worth selling – not only the clean air, lack of crime, natural beauty and abundant recreation.

“Here at the hospital and health centre, we see everything that most rural sites do, but we see a lot of it,” he says. “Every week we have an urgent transfer out, for an acute heart attack or serious trauma. It’s very interesting medicine for someone who is brand new and wants to develop their skills, or someone who wants to keep up their existing skills.”

A cohesive quartet

Dr. Card’s hard sell began to yield results. He aroused the curiosity of Dan Penman, a Vancouver native who earned his M.D. in the Vancouver Fraser Medical Program and then became a family medicine resident in Prince George.

“I came out for a couple of visits, and liked what I saw,” Dr. Penman says. “This setting was ideal for me because there is no specialist back-up on site, so we’re doing a lot more emergency medicine, even internal medicine, as well as follow-up.”

Dr. Penman’s arrival came not a moment too soon, because the remaining South African physician left for Vancouver. Then, like a pyramid scheme, Dr. Penman was roping in one of his former colleagues, Matt Robichaud.

With his arrival, Mackenzie had a cohesive quartet of physicians.

“We’re all fishing buddies here,” Dr. Penman says. “Sometimes we joke that this is an extension of our residency, because it feels like that.”

But it didn’t end there. As Dr. Card’s wife headed back to work after a maternity leave, he wanted to reduce his hours. So they recruited Jyoti Seshia, another Prince George family medicine resident, who was willing to share Dr. Card’s slot.

“James did an excellent job of promoting the community,” says Dr. Seshia, who earned her M.D. at the University of Manitoba. “He had locumed around quite a bit, and had a good sense of the work environment in different places. He reinforced that I would be well-supported – people back each other up for second opinions or help with difficult cases, even if they’re not officially working.”

With Dr. Mackenzie and Dr. Robichaud eventually deciding that they, too, wanted to work part-time, two more physicians arrived in November to fill the gap – the husband-and-wife team of Ian and Lindsay Dobson, both former UBC medical students.

“Ian was doing locums with us, and basically saw a tight-knit group of physicians who support each other, and a practice where he could do a lot of emergency medicine,” Dr. Card said.

Playing the long game

Dr. Card also convinced the Faculty of Medicine to include Mackenzie on rotations of medical students and second-year residents. Each resident conferred an immediate benefit, in the form of an extra pair of hands to shoulder the patient load. But both residents and medical students are part of Dr. Card’s long game – cultivating younger talent in case another opening comes up, so

Mackenzie won’t have to confront the desperate situation it faced just three years ago.

“A medical student I had here from a couple of years ago talked with a friend of hers about us, and that friend came up here for rotations during her residency in Nanaimo,” Dr. Card says. “Now she is coming up for locums. So we can see that the depth of our strategy is starting to pay off.”

In a broader sense, Mackenzie is also seeing a payoff.

Like other towns in northern B.C., it contributed to the Northern Medical Programs Trust, which assists with travel and accommodation for medical, nursing and physiotherapy students as they do their rotations in the region. So the townspeople were vested – in a very real sense – in distributed education.

And what did they get in return?

The Northern Medical Program was responsible for setting James Card down the road to Mackenzie. And the Prince George family medicine residency program – which expanded last year from 11 to 15 residents – provided Dr. Card with a crop of young physicians to bring along with him.

“All of the communities in the North put some of their money into the medical program, because they believed that it would benefit them. And it’s benefiting us now, more than ever,” said Stephanie Killam, who ended her term as Mackenzie’s mayor in November. “We’ve welcomed these doctors into our homes, and they’re becoming part of our community.”

Barbara Crook, who as Mackenzie’s health administrator for the past decade has been an up-close witness to the town’s turbulent medical fortunes, no longer fears that ambulances will need to bypass the town’s emergency room.

“I’m blessed every day I come to work now, knowing my community is covered,” Crook says. “We have a great team here. Having Dr. Card as that cornerstone of a physician brought a lot of peace for all of us.”

2014 marks the 10 year anniversary of the expansion and distribution of the Faculty of Medicine’s MD Undergraduate Program. To learn more, visit BCMD10, a new microsite that chronicles the program’s history, challenges and successes.