A protein, called SIGIRR, is produced by the cells that line the intestines. It supresses the cells’ immune response to bacteria.

“We expected that when SIGIRR was removed, our intestines would trigger a stronger immune response to a gut infection, affording us more protection against the infection,” says Bruce Vallance, an Associate Professor in the Department of Pediatrics and a scientist at the Child & Family Research Institute at BC Children’s Hospital. “Instead, the stronger immune response also killed the resident bacteria in our gut.”

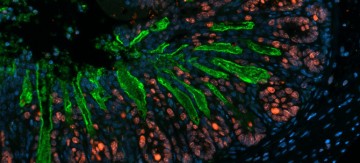

As it turns out, gut flora – microorganisms that live in our digestive tract – literally compete for living space and nutrients with some invading bacterial pathogens, like Citrobacter rodentium, the one used in this study. Without our gut flora, harmful bacteria that are more resistant to our immune system can rapidly take over and wreak havoc, causing infection or even Inflammatory Bowel Disease.

By dampening our immune response to allow the good bacteria to take up residence in our gut, SIGIRR maintains the delicate balance that keeps our gut healthy, says Dr. Vallance, who holds the Foundation for Children with Intestinal & Liver Disorders (CH.I.L.D.) Chair in Pediatric Gastroenterology.

“Maintaining a healthy gut flora by limiting antibiotic use or even taking probiotics may be important in fortifying this important defense barrier in our intestines.”