To prevent cognitive overload, an instructor dissects neuroanatomy, and radically reassembles it.

A gentle chime sounds over the PA system of the Multi-Purpose Lab, signaling the start of another weekly learning session in Brain & Behaviour.

But instead of starting off with an information-laden lecture, UBC’s second-year medical students log in at their computers to answer a few multiple-choice questions, including, “The primary visual area of the cortex is supplied by…” and “A lesion of the right optic tract will result in…”

On three of the questions, 90 per cent or more of the students answer correctly; on the fourth, 69 per cent select the right response.

Claudia Krebs is pleased. Though it’s just one small piece of evidence, her experiment in flexible learning seems to be working.

A Senior Instructor in the Department of Cellular and Physiological Sciences, Dr. Krebs has dramatically revamped the neuroanatomy component of Brain & Behaviour. The re-working was one of 19 projects selected for funding by UBC’s Flexible Learning Initiative, which aims to give students more choice in when, where and how they learn.

Overcoming “neurophobia”

Dr. Krebs sought to repair what she considered the major flaw with neuroanatomy: Students were being bombarded with information through lectures, not absorbing much of it, and getting very frustrated in the process.

For years, Dr. Krebs suspected that her efforts to make her lectures more approachable weren’t overcoming students’ “neurophobia” – the fear of learning about the brain and nervous system, in all their complexity.

“I’ve been trying to tackle this for a long time,” she says. “I introduced more clinical examples, and my fellow teachers complimented me on how I presented it. But when a former student recounted how she would leave each week’s lab in tears, I realized it wasn’t enough. I had to come up with some way they could manage it better, so I could lead them through it step-by-step, but at their own pace.”

Supported by a $60,000 grant from the Flexible Learning Initiative, Dr. Krebs sought to abandon the structure of the weekly lab: a 20- to 30-minute lecture and anatomical dissection led by her, followed by students using specimens at their tables to go over what she had just covered – identifying different parts, remembering their respective functions, seeing how they related to other parts.

She also wanted to slim down the thick, didactic lab manual, which was essentially a softcover textbook, and make it into more of a workbook. And the information that manual once imparted would become more interactive, animated, even more stylized.

Close-ups and mood music

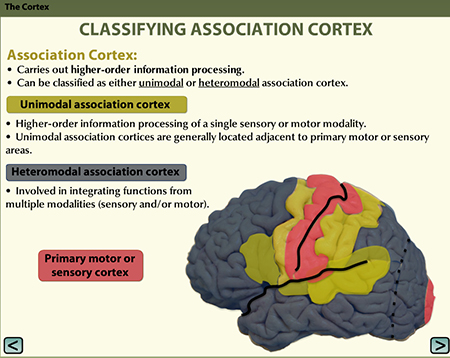

Taking advantage of the dynamism and eye-candy appeal of digital graphics, she and her team – including people from the Department of Cellular and Physiological Sciences, MedIT, and UBC’s Centre for Teaching, Learning and Technology – created a set of online slides for each lab.

With each click, a picture appears with an explanatory block of text, followed by pop-ups pointing to various parts of the brain and spinal cord. Many of the slides incorporate anatomical watercolours from the 1950s by Nan Cheney, a painter, confidante of Emily Carr, and the Faculty of Medicine’s first medical illustrator. Practice slides ask students to drag and drop labels to various parts or to answer multiple choice questions.

Still other information is conveyed through lecture and dissection videos. But no stiff instructors droning on at a podium here – the videos exploit various camera angles, close-ups, soft lighting, and science-y mood music.

Riffing on the Cheney illustrations, the videos have a deliberate retro style. Professor Wayne Vogl draws on a chalkboard (or points to parts of a live human model) while he talks, and Dr. Krebs wears her great-aunt’s pearl necklace while dissecting a spinal cord.

Students are expected to go through the modules and videos before each lab, taking as much time as they need and going back over something that isn’t quite catching, so they avoid what Dr. Krebs calls the “cognitive overload” of her lectures. (All of this material is available on neuroanatomy.ca.)

When students arrive for that week’s lab, they complete the short “readiness assessment test” (or R AT), then break into small groups to answer the questions from the lab manual as Dr. Krebs and other instructors roam the room. So the initial, nuts-and-bolts learning is done at home, while the reinforcing “homework” is done in class.

“The talking head is now on the web, so real interaction can happen in class,” Dr. Krebs says. “They are prepared, so we can go in-depth and explore their questions. And every student will have different questions. That, for me, is what universities are all about – it’s about the exchange, not me reading to them.”

More work on the front-end

Claudia Krebs (in green lab coat) discusses the finer points of the spinal cord with studnets in a neuroanatomy lab. Photo by Martin Dee

Although the students experiencing these revamped neuroanatomy lessons have little basis for comparison, they know it’s a new approach, and most of those interviewed say it’s working for them. Martha Balicki’s comments were typical:

“I’m more engaged. I’m learning it, as opposed to letting it wash over me and then panicking when I realize I don’t understand it. By asking me questions and forcing me to think through the answers, they’re making me apply the learning. It’s a lot more work on the front-end, but I think it will be a lot less work on the back-end when it comes to exams.”

A more quantifiable measure of the new paradigm will come from student surveys and exam results. One particularly telling indicator for Dr. Krebs will be how students fare on the questions about bladder function.

“In past labs, we didn’t even get to bladder function, or it would be tagged on at the end, when everyone was exhausted, so it came down to, ‘OK, the bladder doesn’t work when you have a spinal cord injury,’” Dr. Krebs says. “Every year we include questions about it, and no one gets it right, even though we tell them they need to know it. They weren’t learning it. This year, from my interactions with students in the lab, I’m almost certain they will perform well on those questions, because they have an understanding of it.”

But Dr. Krebs already has one positive, and surprising, result: For the first time, she has won the Year 2 Teaching Excellence Award.

“I was expecting my ratings to drop! That’s usually what happens when you implement curricular change,” she says. “I guess this was one change that was long overdue.”