Another culprit for obesity: Too much insulin

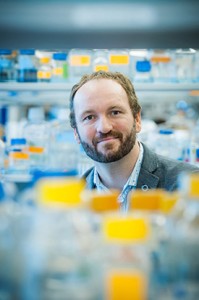

A serendipitous discovery by Associate Professor James Johnson could overturn widely accepted notions about healthy eating habits.

The study, published in Cell Metabolism, examined the role of insulin, the hormone that allows the body to store blood sugar for later use as an energy source. Dr. Johnson, in the Department of Cellular and Physiological Sciences, gave a high-fat diet to two groups of mice: A control group of normal mice and another group bred to have half the normal amount of insulin.

The control group, as expected, became fat. But the low-insulin mice were protected from weight gain because their fat cells burned more energy and stored less. The lean mice also had less inflammation and healthier livers.

Dr. Johnson concluded that extra insulin produced in the normal mice by the high-fat diet caused their obesity, which strongly suggests that mice – and, by extension, humans – may make more insulin than they need.

The findings may mean that the key to maintaining a healthy weight is to continually return insulin levels to a healthy baseline by extending the gaps between meals and ignoring the widespread recommendations to consume small amounts throughout the day. In other words, cut out the snacks — and make sure not to overcompensate at mealtime.

“As crucial as insulin is for storing blood sugar, it can also be too much of a good thing,” Dr. Johnson says. “If we can maintain insulin levels at a happy medium, we could reverse the epidemic of obesity that is a risk factor for so many ailments — diabetes, heart disease, and cancer.”

While existing insulin-blocking drugs could prevent weight gain, they carry serious side effects that outweigh their benefit. Further research might lead to drugs that block excess insulin production or blunt its effect on certain targeted tissues. Dr. Johnson also has plans to study a number of different diet types to determine which approach is most effective at maintaining healthy insulin levels.

Grading the graders

The best gift you can give a stand-up comedian is to subject his audience to an atrocious warm-up act.

Kevin Eva showed that the same is true for medical residents.

Dr. Eva, a Professor and Director of Educational Research and Scholarship in the Department of Medicine, worked with researchers at the University of Manchester to see if clinical educators’ grading of younger doctors could be influenced by the quality of those they had previously evaluated.

In the study, published in JAMA, physician-educators in England and Wales were asked to grade videos of young doctors in their first year of post-graduate training. The trainees in the videos followed scripts representing three levels of performances – good, poor, and borderline – as they interviewed and examined actors portraying patients.

Some educators were “primed” by viewing the good performances while others viewed the poor performances. Then both groups were compared on their grading of the borderline performances.

Educators who had been primed by poor performances consistently gave better grades to the borderline performers than those who had just watched the good performances. Depending on the patient case, the grades were 30 per cent to 100 per cent better.

“This experiment shows that judging someone’s performance – whether it’s clinical skills, essay-writing, or figure skating – is likely to be relative, and that we can’t assume that examiners are working from a fixed, absolute standard, as is expected in current models of education,” says Dr. Eva, a Senior Scientist at UBC’s Centre for Health Education Scholarship.

“While such assessments are unavoidable in determining whether a student has mastered the required competencies in a field like medicine, we need to take steps to minimize contrast bias — perhaps by continually mixing up the order of the people being examined,” Dr. Eva says. “This is one of the reasons it is important to ensure that there are a sufficient number of evaluations — the more data points, the more reliable the aggregate score will be.”

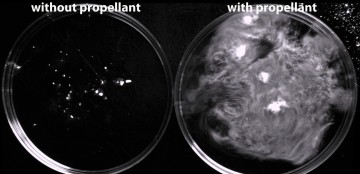

A self-propelled coagulant

Christian Kastrup, an Assistant Professor in the Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, has invented a mechanism for getting blood- clotting treatments to the source of bleeding.

Dr. Kastrup’s idea involves micro-sized coagulant particles that are surrounded by a water-sensitive propellant, which releases gas and energy when it comes into contact with blood. The resulting reaction drives the particles at a high velocity (more than 10 cm/sec) upstream against the flow of blood, potentially allowing them to penetrate deep into areas of bleeding — particularly post-partum, but also in cases of trauma.

“If we put these particles onto a wound, the particles will fly all over, including upstream through blood, to the site of the hemorrhage, where they can stop bleeding from occurring,” says Dr. Kastrup, who also is a member of the Michael Smith Laboratories and the Centre for Blood Research.

With a $100,000 grant from the federally-funded Grand Challenges Canada, Dr. Kastrup plans to use animal models to determine the optimal combination of propellant and coagulant, and the optimal size of the particles necessary for penetrating deep into areas of bleeding without entering the circulatory system. He will also produce a feasibility study showing how this topical treatment can be distributed and used by non-experts in developing countries, presumably through commercial partners.

“It will have simple instructions, such as, ‘If you see a lot of blood, pour powder over the site of bleeding,’” Dr. Kastrup says.

The lingering damage of concussions

Concussion-related changes to brain structure and function persist well beyond the initial trauma — leaving open the possibility that adolescent athletes could be returning to sports before their brain injuries have fully healed.

In a study published in Pediatric Neurology, Faculty of Medicine researchers used advanced imaging and a common concussion assessment technique to examine brain structure and function in a dozen adolescents who had experienced at least one sports-related concussion in the previous two months, and compared them with 10 otherwise healthy, non- concussed adolescent athletes.

In a study published in Pediatric Neurology, Faculty of Medicine researchers used advanced imaging and a common concussion assessment technique to examine brain structure and function in a dozen adolescents who had experienced at least one sports-related concussion in the previous two months, and compared them with 10 otherwise healthy, non- concussed adolescent athletes.

“The imaging results, which captured the movement of water through the brain, showed that the integrity of white matter was significantly different between the concussed and non-concussed teenagers,” says Naznin Virji-Babul, an Assistant Professor in the Department of Physical Therapy and a scientist in the Brain Research Centre and the Child & Family Research Institute. Postdoctoral fellow Michael Borich analyzed the brain scans.

The brain images, Dr. Virji- Babul says, “were strongly associated” with results from the concussion assessment test, which is used on playing fields and in clinical settings, and measures 22 symptoms, including balance, orientation and memory. But coaches and trainers sometimes dismiss or downplay negative results from such assessments.

“Our research has immediate impact on return-to-play decisions made by physicians and medical personnel, coaches, parents, and the athletes themselves,” says co-author Lara Boyd, a Canada Research Chair in the Neurobiology of Motor Learning and also a member of the Brain Research Centre. “We need age- specific diagnostic guidelines that are applied consistently across the disciplines of neurology, physical medicine, rehabilitation, and sports medicine.”

The researchers are planning future studies to understand the risks of returning to play, and to develop improved clinical practice guidelines in physicians’ management of sports concussions.