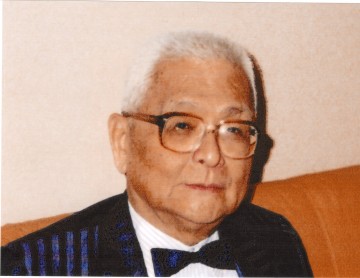

Chew Wei came to Vancouver late in his life, after retiring as a Hong Kong obstetrician and gynecologist.

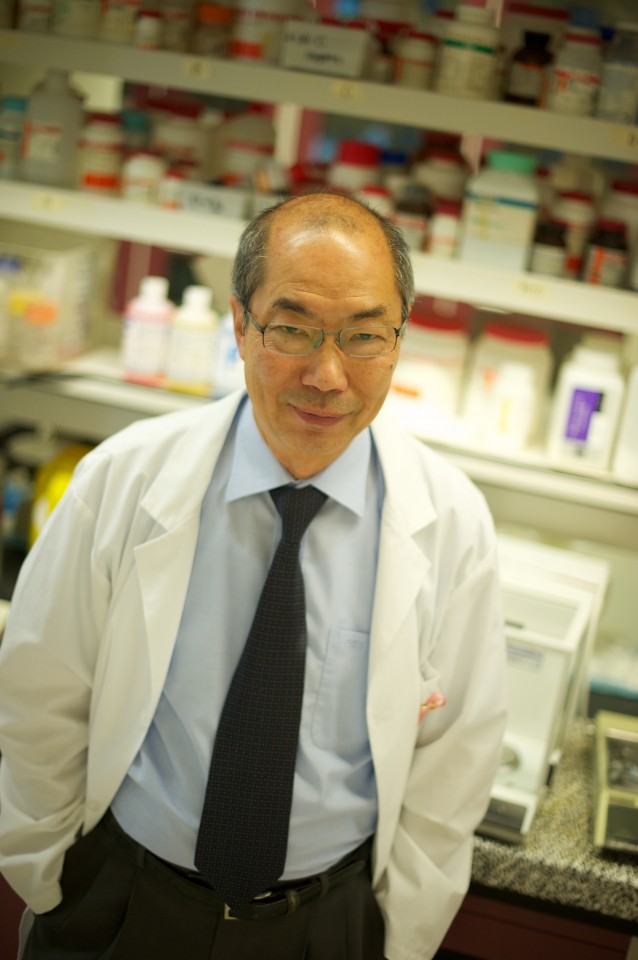

Tak Wah Mak made the same journey in his youth – first to the U.S., then to Canada.

But the two men had much more than their migration in common: They also contributed mightily to cancer research in their adopted homeland.

Dr. Chew, based on his experience as a physician, grew determined to improve outcomes for people with cancer. After his death in 2009, his family and friends in Hong Kong and Malaysia sought to honour his goals by donating $1.5 million to the Faculty of Medicine for a prize in cancer research.

Dr. Mak became an immunologist at the University of Toronto, where in 1984 he discovered, along with U.S. scientist Mark Davis, the T-cell receptor – the component of those immune cells that enables them to detect and destroy bacteria and viruses.

The two men became linked this year, when the inaugural Dr. Chew Wei Memorial Prize in Cancer Research was bestowed upon Dr. Mak. The prize will be given annually to a Canadian physician or scientist who has made a transformational, internationally recognized contribution to the fight against cancer. It emphasizes researchers whose achievements encompass the spectrum of health research, from the laboratory to clinical care to health systems and public policy.

Dr. Mak was chosen to receive the $50,000 prize by an international panel of scientists that provided recommendations to an advisory committee chaired by Gavin Stuart, Dean of the Faculty of Medicine and UBC’s Vice Provost, Health.

“Dr. Mak, as the first recipient of the Dr. Chew Wei Memorial Prize in Cancer Research, has created a fitting benchmark for this award, unequivocally establishing its stature among the most prestigious scientific prizes in Canada,” says Howard Feldman, the Faculty of Medicine’s Executive Associate Dean, Research.

Although the cancer-fighting implications of Dr. Mak’s T-cell receptor discovery were not immediately apparent at the time, clinical researchers have in recent years developed techniques for re-engineering the T-cell receptor gene to target certain cancers. Such treatments, while still in the experimental stage, have yielded dramatic results in some patients, especially those with leukemia and melanoma, in part because T-cells can be far more targeted than surgery, radiation, chemotherapy or hormone therapy.

Since then, Dr. Mak pioneered the development of genetically engineered mice, also known as “knockout mice,” because one or more of their genes have been inactivated. Using this method, he demonstrated the inhibitory effect of a protein called CTLA-4 on T-cells. Those findings led to the development of ipilimumab, a drug that blocks CTLA-4, thus enabling T-cells to proliferate and destroy melanoma cells. Meanwhile, his technique for generating knockout mice – and sharing them with other scientists – fostered tangential discoveries by colleagues around the world.

Dr. Mak has also explored the mechanisms of cell death, thus providing clues about cancer cells’ potential vulnerabilities, and he has described how cancer cells can adapt their metabolism to avoid the body’s own defenses.

Dr. Mak was honoured at a banquet in June attended by the Faculty’s leadership, its top cancer researchers and family and friends of Dr. Chew. One of the attendees included another legacy of Dr. Chew’s mission – Professor of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine David Huntsman, who was named the Dr. Chew Wei Memorial Professor of Gynecological Oncology in 2012, thanks to a $3 million gift from Dr. Chew’s family and friends.