Testing for the human papillomavirus (HPV) can detect cervical precancer earlier and more accurately than the standard Pap test, according to a six-year study involving 19,000 Canadian women.

The findings, published July 3 in the journal JAMA, could give health policy-makers and medical societies the confidence to switch to the automated, machine-based HPV test, because it would provide more reliable results than the 50-year-old Pap test, and would not have to be done as frequently.

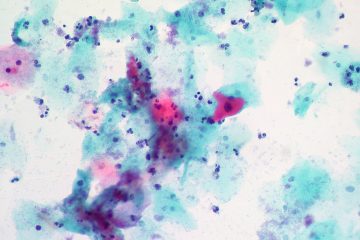

The HPV test, which became available over a decade ago, uses a machine to measure molecular signs of the virus. The Pap test, in contrast, relies on a pathologist or trained technologist using a microscope to look for abnormal cells.

Currently, U.S. cervical cancer screening involves both tests together, while most Canadian women only get a Pap test. A few countries are switching to HPV testing for primary screening, but most are waiting for more definitive evidence about its effectiveness as standalone test.

The Canadian study, led by scientists from the University of British Columbia, BC Cancer and the B.C. Centre for Disease Control, was the first clinical trial designed to compare the effectiveness of the two tests.

“Our results, by demonstrating the increased accuracy of HPV screening, show that the HPV test will detect pre-cancerous lesions sooner so they can be removed or destroyed before becoming cancerous,” said lead author Gina Ogilvie, a Professor in the UBC School of Population and Public Health and senior research advisor at BC Women’s Hospital + Health Centre. “When the Pap test was introduced a half-century ago, it dramatically lowered the number of women who died from cervical cancer. But the HPV test can push that number much closer to zero.”

The HPV test works because almost all cases of cervical cancer are caused by the virus. In most cases of infection, the body gets rid of the virus without any ill health effects. But in a small percentage of infected people, the virus spurs some cells to become cancerous.

The Canadian study, from 2008 to 2016, recruited women from the Vancouver metro area and greater Victoria, with half of them receiving only the HPV test at first. If they tested negative for the virus, they returned four years later and underwent both tests.

The other half – a control group – received the Pap test, and if the results were negative, were re-tested two years later. If they tested negative again, they returned at the four-year mark, when they, too, received both tests.

In either arm of the study, if a woman tested positive and was later found to have precancerous cells, she was referred for treatment.

At the study’s endpoint four years later, fewer of the remaining women in the HPV test group were found to have precancerous cells, because the HPV test had been identifying more women for closer examination, with possible biopsy and treatment. As a result, women who were screened for HPV at the start were almost 60 per cent less likely to have a precancerous lesion four years later, compared to women who received Pap tests.

The HPV test produces results that are more consistent, and can be generated in half the time or less that Pap tests normally require, said co-author Dirk van Niekerk, the Medical Leader of BC Cancer’s Cervix Screening Program and a UBC Clinical Assistant Professor of Pathology and Laboratory medicine.

“This study showed that the HPV test is reliable enough to give peace of mind to women who have tested negative, and that those results are good for at least four years,” Van Niekerk said. “That means HPV testing could be done less frequently than Pap tests are currently done, and with more women getting treatment at the earliest possible opportunity.”