Each spring and summer, Ed Conway leaves the sun kissed banks of Vancouver to join his wife Ruth Hoffman in the bustling city of Kampala, Uganda. An accountant who is passionate about development work, Ruth has devoted her life to empowering vulnerable groups by teaching them financial literacy and connecting them with limited resources, such as mobile libraries.

Inspired by his wife’s natural goodwill, Dr. Conway wondered how he could also give back.

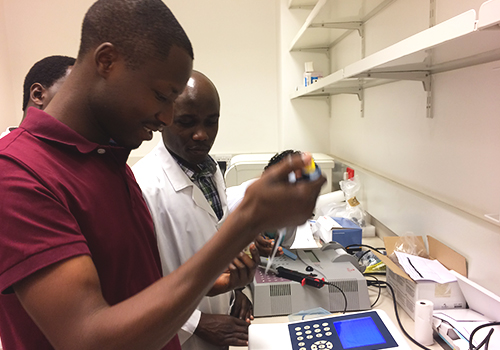

Ed Conway with the technologists from the hemophilia team in Kampala

A hematologist and director of UBC’s Centre for Blood Research, Dr. Conway reached out to Kampala’s Makerere University and began teaching medical residents. It was during this time when he met Agnes Kisakye, a social worker and executive secretary of the Hemophilia Foundation of Uganda, who travels around the country leading awareness campaigns and helping people get better care.

“Her nephew has hemophilia and suffers from crippling arthritis due to limited medical expertise and resources,” says Dr. Conway. “As a result, Agnes is dedicating her life to advocating for improved health care and educating people about the condition, as awareness is so low in Uganda.”

Hemophilia is a rare genetic blood disorder that impairs the body’s ability to make blood clots. Affecting only boys, children with the disease can suffer frequent major bleeds into the joints, muscles, gut or even the brain. Before treatment became available in the developed world in the 1960s, those with the disorder would become crippled at a very young age, many dying in their early teens.

“With treatment, children with hemophilia in Canada can expect to live a full life,” he explains. “But not everyone has the same access to medical care as people do in North America and Europe.”

Canada and Uganda have similar population sizes, with each country having roughly 40 million people. In Canada, there are about 4,000 people diagnosed with hemophilia. In Uganda that number hovers at 150.

“The numbers should be the same because it’s a genetic disease,” he says. “There are only five hematologists in all of Uganda who are tasked with diagnosing and treating everything from leukemia to anemia. That means that most of those with rare disorders such as hemophilia, go undiagnosed.”

When he asked Agnes what was needed to help connect more people with care, her answer was clear – Ugandans have free access to treatment, but making the diagnosis is a major challenge. The machines used to test for the disorder are either unavailable or simply too expensive.

The plan

During the months following his meeting with Agnes, Dr. Conway reached out to the global hematology community for advice. He consulted with colleagues and hematologists with years of experience working in under serviced areas. He met with local physicians and hemophilia care-givers, and spoke to representatives of the World Federation of Hemophilia (WFH).

With their help, he mapped out a low-cost plan that would be completely sustainable and self-sufficient.

“We went back to the basics,” he says. “Because sometimes going backwards is going forwards.”

The plan was to get a semi-automatic coagulation analyser – an older diagnostic model that was routinely used in the 1980s.

“It’s not as modern but it works just as well,” says Dr. Conway. “It’s a very easy and inexpensive machine to run and it uses generic reagents (the substance needed to run the test) which are completely affordable. The entire machine and a two-year supply of reagents would cost $7,500.”

A technologist training to use the new coagulation analyser

To raise the funds, while at the same time increasing awareness, he launched an online crowdfunding campaign.

The reaction was overwhelming. Not only did he surpass his target — but Diagnostica Stago, the company that makes the coagulation analysers — donated a second machine and provided free training for the technologists. The WFH also offered a lifetime supply of reagents.

“I was completely blown away by people’s generosity,” says Dr. Conway. “I had no idea of what to expect and the experience was really heartwarming.”

With the supplies en route, Dr. Conway recruited a hematologist at the Ugandan Cancer Institute who agreed to help build and lead the hemophilia program. Soon after, representatives from Stago sent in their team to install one of the machines and train five technologists.

Since October, a hemophilia clinic has been established at Makerere University, and 10 children have been tested and diagnosed.

“There are two types of hemophilia, so it’s crucial to make that diagnosis because the treatments are different,” says Dr. Conway. “Now these children can get the appropriate treatment and can be better monitored going forward.”

“For such a small amount of money, the impact this program is having is incredible.”

The second machine will be installed in a separate location in Uganda as part of a growing effort to connect more children with care.

The future vision of hemophilia care in Uganda

While more children will be receiving the treatment they need, Dr. Conway says there are still challenges, namely transportation and a lack of awareness about the disorder.

“Seventy per cent of Uganda is rural and the roads are so bad that a lot of people can’t make it to the hospital,” he explains. “Even if you live in the city, it can be difficult to get around, particularly during the rainy seasons.”

Children with hemophilia need up to three injections per week – a tall order for families who can’t afford to take the time off work to travel to the hospital. Refrigerators are also a luxury that many households don’t have, so storing the medication is another obstacle.

The second coagulation analyser will hopefully help ease this gap but it will not connect the most vulnerable with the care they need.

A road in Kampala

Dr. Conway and the Ugandan team are hoping to change that by bringing the services to them.

“Our idea is to hire boda-boda (Vespa) drivers to bring nurses to rural communities so they can provide home treatments,” he says. “We know it wouldn’t cost much, so right now we are looking at all the logistics involved. They’ll start small with just a few patients and once the team is comfortable managing it, they will scale up.”

For that, they will likely need some start-up funds, for which Dr. Conway hopes to launch another online fundraiser.

Just as his wife has learned over the years, Dr. Conway says the experience has taught him how important it is to help people help themselves by providing education and training, so that they can lead and run the projects themselves. He also says that his motivation and future vision for the program is the same as the Ugandans.

“I want what they want – to ultimately see that hemophilia care in Uganda is as good as it can be,” he says. “So their kids can lead healthy and full lives, as ours do in Canada.”

Related Stories: Giving Back

Improving maternal health at home and abroad

A conversation on global maternal health with UBC Midwifery Instructor Cathy Ellis. Read More >

A lifetime of lifesaving leads a faculty member to Bangladesh’s “drowning fields”

Clinical Professor Steve Beerman aims to reduce childhood drowning in Bangladesh. Read More >

Changing lives — one diagnosis and lesson at a time

The vast majority of adults with ADHD don’t even know they have it. Drs. Gurdeep and Anita Parhar are working to change that. Read More >

Giving back by taking rubbish – and recycling it

SPPH Professor Karen Bartlett creates own initiative to shrink the school’s environment footprint. Read More >

MD student Max Moor-Smith talks about his summer research project in India

Second-year medical student Max Moor-Smith shares his experience providing health education for children in Spiti Valley, India. Read More >