A Faculty of Medicine researcher has discovered a biochemical method cells use to internally compartmentalize themselves. In the process, he may have revealed why a known genetic mutation leads to the incurable, devastating disease amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS).

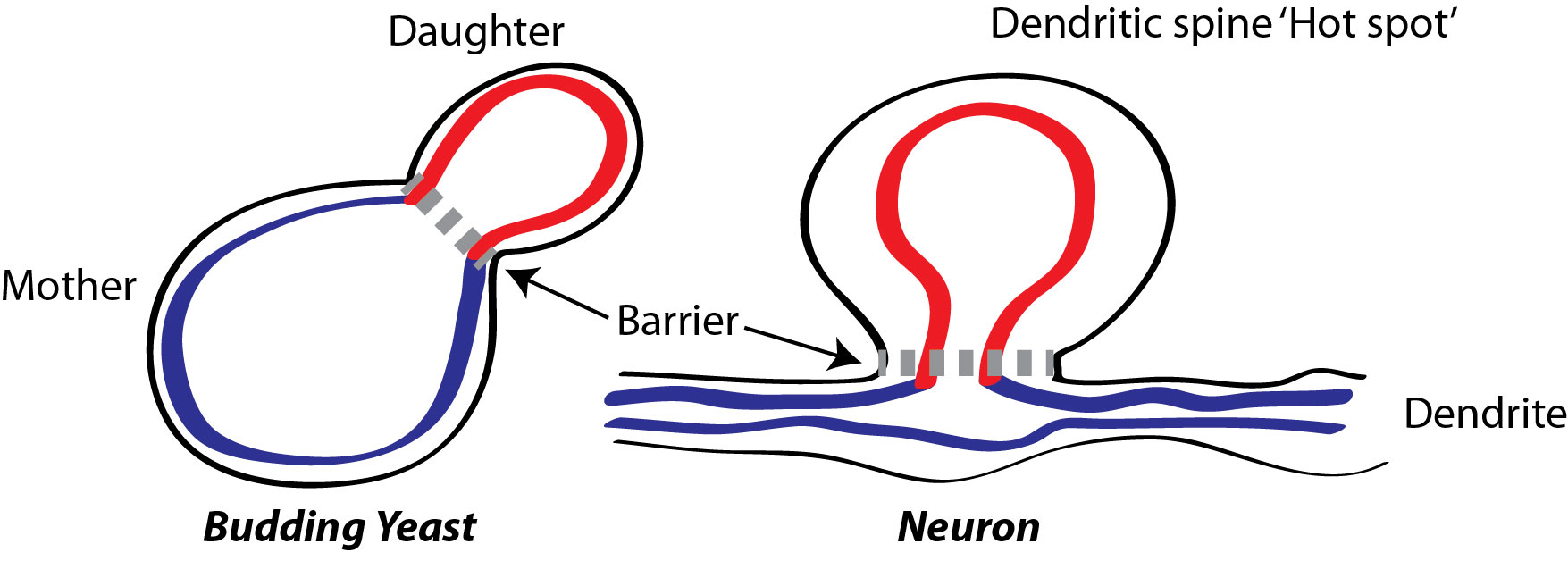

Associate Professor Christopher Loewen, in the Department of Cellular and Physiological Sciences, has used yeast cells to show how certain proteins in the outer membrane link up with proteins in the inner membrane to create an internal barrier.

Dr. Loewen’s findings, published July 31 in the journal Cell, were based on yeast reproduction, in which a cell produces an identical copy of itself (known as a daughter) by squeezing off some of its own material. The creation of a barrier between the mother and the daughter prevents mixing of unwanted material between mother and daughter and helps to concentrate the new material in the daughter.

The firing of motor neurons is also dependent on such biochemical barriers. The branches of neurons, known as dendrites, are primed to receive signals from neurotransmitters released by neighboring neurons. Effective nerve transmission depends on concentrating the signals produced by the neurotransmitters, such as glutamate, in certain “hot spots” that protrude from the surface of the dendrites.

“If you don’t restrict the biochemistry to these hotspots, it will diffuse into the tangles of dendrites,” says Dr. Loewen, a member of UBC’s Life Sciences Institute and the Brain Research Centre of UBC and Vancouver Coastal Health. “It would be so diluted that it wouldn’t be able fire the neuron.”

ALS (also known as Lou Gehrig’s disease) causes people to lose control of their muscles. In most cases, they die within three to five years after symptoms first appear.

Christopher Loewen’s has discovered a mechanism for creating internal barriers in both yeast cells and neurons, helping to compartmentalize cellular material and chemical reactions. Illustration by Christopher Loewen

One of the dozen mutations that lead to ALS affects production of a protein called VAP-B, which is verysimilar to one of the linking proteins in yeast identified by Dr. Loewen. He speculates that VAP-B may be a crucial part of the internal barrier isolating the surface hot spot from the rest of the dendrite. Without VAP-B, the barrier between the hot spot and the rest of the dendrite becomes porous, the glutamate signal leaks out, and the neuron won’t fire.

The next step for Dr. Loewen is to test that theory in mice or rats with the VAP-B mutation. He and Associate Professor Shernaz Bamji will zero in on the hot spots of their dendrites to see if signaling at those points is degraded.

“If we find evidence that signals aren’t getting through, then we will be much closer to understanding how the VAP-B mutation leads to the loss of muscle control in ALS,” Dr. Loewen says.