Revolutionizing the recovery journey

How translational research is improving the lives of heart transplant patients

Christine Boutin was in the early months of her first pregnancy when she received the news from her doctor that her heart was failing.

By her daughter’s fourth birthday, complications stemming from Christine’s heart condition left her struggling to perform routine tasks. On walks in her neighbourhood she would look for resting spots along the way—anywhere to catch her breath. And then, one day after her daughter took a tumble and scratched her knee at the playground, Christine realized she could no longer carry her daughter home.

“I remember her reaching up with both arms and I had to tell her I just couldn’t pick her up. That realization was really hard. I kept thinking that I couldn’t live like this,” recalls Christine.

February is Heart Month

Cardiovascular disease is the number one cause of death for Canadians.

By the spring of 2019, Christine’s conditioned had worsened and she was placed on B.C.’s heart transplant list. Then, a few months later, encouraging news arrived—she would be the recipient of a new heart and precious chance on life.

But the recovery journey for heart transplant patients, like Christine, is not easy.

In addition to the physical and psychological toll from undergoing surgery, patients need to be closely monitored to ensure they are not at risk of rejecting their new heart—a common occurrence in the first year after receiving a donor heart and one that has dire consequences.

Right now, the only way to confirm or rule out rejection is for patients to undergo up to 15 heart biopsies in the first year alone, the period when the risk of immune rejection is highest. The procedure—whereby heart muscle tissue is extracted using a tweezer-like instrument, which is threaded from the patient’s neck to their heart through a hollow tube inserted into their blood vessel—is invasive, causes great stress and discomfort, and comes with its own risks, including potential injury to the patient’s new heart.

But now, UBC researchers are on the cusp of transforming the recovery journey for future heart transplant patients. Using genomics, they are in the advanced stages of developing a simple blood test that could detect early signs of rejection.

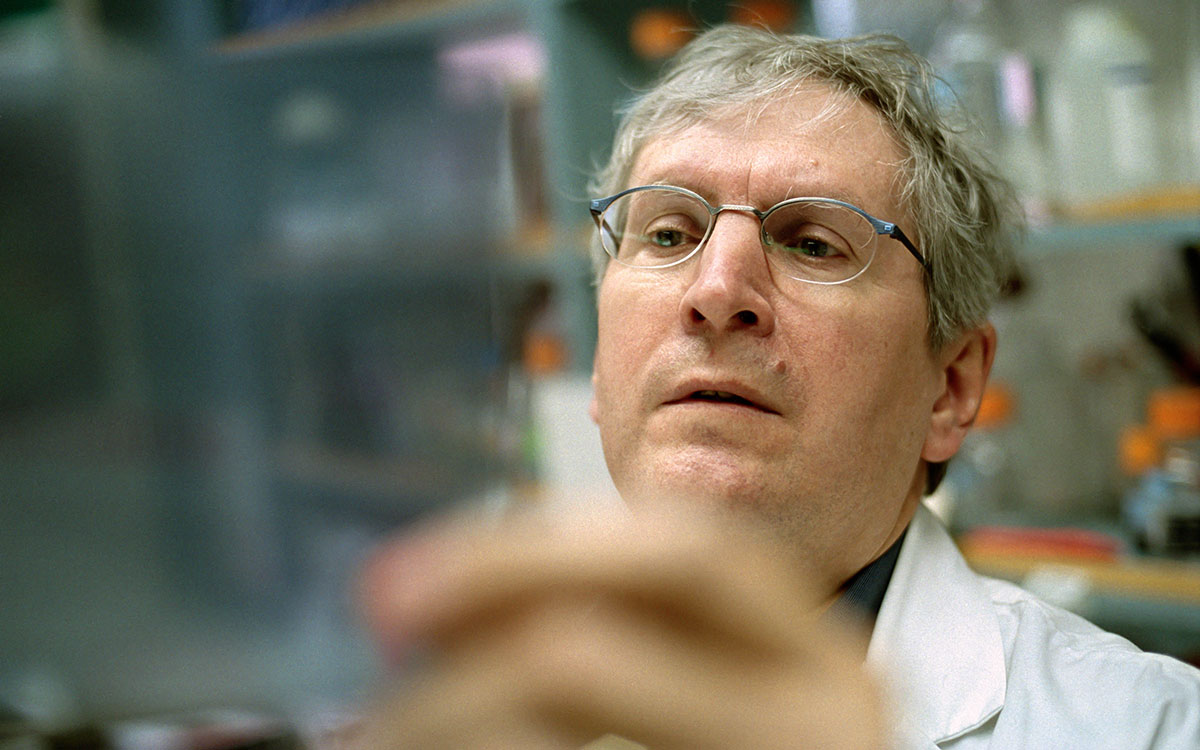

“This test promises to be a revolutionary tool for early detection, and it offers a chance for patients to eliminate the need for a biopsy altogether,” says UBC’s Dr. Bruce McManus, professor emeritus in the faculty of medicine’s department of pathology and laboratory medicine and former CEO of the Centre for Excellence for Prevention of Organ Failure (PROOF), which is co-hosted by UBC and Providence Health Care.

The diagnostic test in development—known as HEARTBiT—would measure the abundance of a handful of genes expressed in a sample of the patient’s blood, enabling the detection of a patient’s risk of acute cellular rejection (the most common form of rejection, whereby a type of immune cells, called T cells, attack and damage the heart tissue).

Dr. Bruce McManus

Improving recovery and reducing healthcare costs

Once available, HEARTBiT would enable heart transplant patients to be tested for rejection during routine bloodwork performed anywhere in the province. Currently, the only place in B.C. that patients can receive a heart biopsy is Vancouver.

“If you’re a patient who lives outside of Vancouver, in Kelowna or 100 Mile House for example, having a biopsy is disruptive to your personal and working life,” says Dr. McManus.

Asmaa Anwar, who lives in the seaside town of Sidney on Vancouver Island, is one of those patients.

Since receiving a heart transplant in the summer of 2019, Asmaa has received more than 15 biopsies —nearly half have required travel and an overnight stay in Vancouver.

And while Asmaa is incredibly grateful for the connections and friendships she has made with other heart transplant patients during her biopsy appointments, she believes a simple blood test would go a long way in reducing the anxiety that surrounds the invasive procedure.

“A blood test would be less taxing on the patient, and the medical system,” says Asmaa.

In fact, once rolled out, the made-in-B.C. test would lead to a drastic reduction in costs for the healthcare system.

According to health economists working with the team, HEARTBiT would reduce current costs associated with monitoring rejection in heart transplant patients by more than 50 percent.

“That is not a trivial amount,” says Dr. McManus, who began the journey of investigating how to create a non-invasive diagnostic test for heart transplant patients nearly two decades ago.

HEARTBit would reduce current costs by more than 50%

Patients could be tested for rejection anywhere in the province through a simple blood test

The journey from bench to bedside

The development of HEARTBiT has required years of rigorous work and dedication, but also wide-sweeping collaboration with scores of life scientists, economists, data scientists and computational biologists, like UBC graduate Casey Shannon.

Using machine learning, the team has scoured through vast amounts of patient data to identify the specific genes, or biomarkers, that can help determine rejection risk after a heart transplant.

“It’s a needle in a haystack kind of problem,” says Shannon. “We had to find the handful of genes in the blood that could give us the information we were looking for.”

The team has successfully narrowed down the list of potential genes from 30,000 to just nine that can help pinpoint a patient’s risk of rejection.

“HEARTBiT is a prime example of translational research, taking an idea from discovery to the clinic to transform patient lives,” says one of HEARTBiT’s creators, Dr. Robert McMaster, professor in the faculty of medicine’s department of genetics and Vice Dean, Research.

Now, one of the final steps before the test can go through regulatory approval is validation of the test in a laboratory setting—a meticulous process being led by UBC postdoctoral fellow Dr. Ji-Young Kim.

“It’s one thing to say that this test is relevant to the clinic, it’s quite another to prove that it’s reliable and that it can offer results that you can believe in,” says Dr. Kim.

Each day, Dr. Kim measures HEARTBiT’s performance against various parameters, investigating everything from how using a different testing compound to storage conditions, and time of day may impact the result of the test. She repeats the process hundreds of times in order to exhaust all parameters in different combinations. The results of the team’s scrupulous analysis and testing were published in the Canadian Journal of Cardiology (November 2019) and Clinical Chemistry (July 2020), the flagship journal in laboratory clinical biochemistry.

Patients at the heart

Despite the challenging work of bringing a new blood-based diagnostic test to clinic, the HEARTBiT research team is inspired by the promise of one day being able to deliver better care to patients.

“The patients are the reason we get up every morning,” says Dr. McManus. “Our work is entirely driven by the desire to improve the recovery journey for heart transplant patients. And without them—without their participation, their samples, and their engagement—we would have nothing.”

For Christine, who now wears a scar on her neck from repeated biopsy incisions, the prospect of eliminating or reducing the number of biopsies for future heart transplant patients is game changing.

“Each biopsy becomes progressively more painful,” she says, recalling the anxiety she experienced undergoing the procedure.

And while Christine’s road to recovery continues, most days she is focused on the simple, yet significant improvements to her health, and time spent with her daughter.

“The other day my daughter turned to me and said ‘Ready, set, go! I had never raced her to anything before in my life, and I just started to run.”

“Of course I let her win—but, for the first time, I was right on her heels.”

Share this Story

Published: February 8, 2021