Pushing the boundaries of spinal cord research

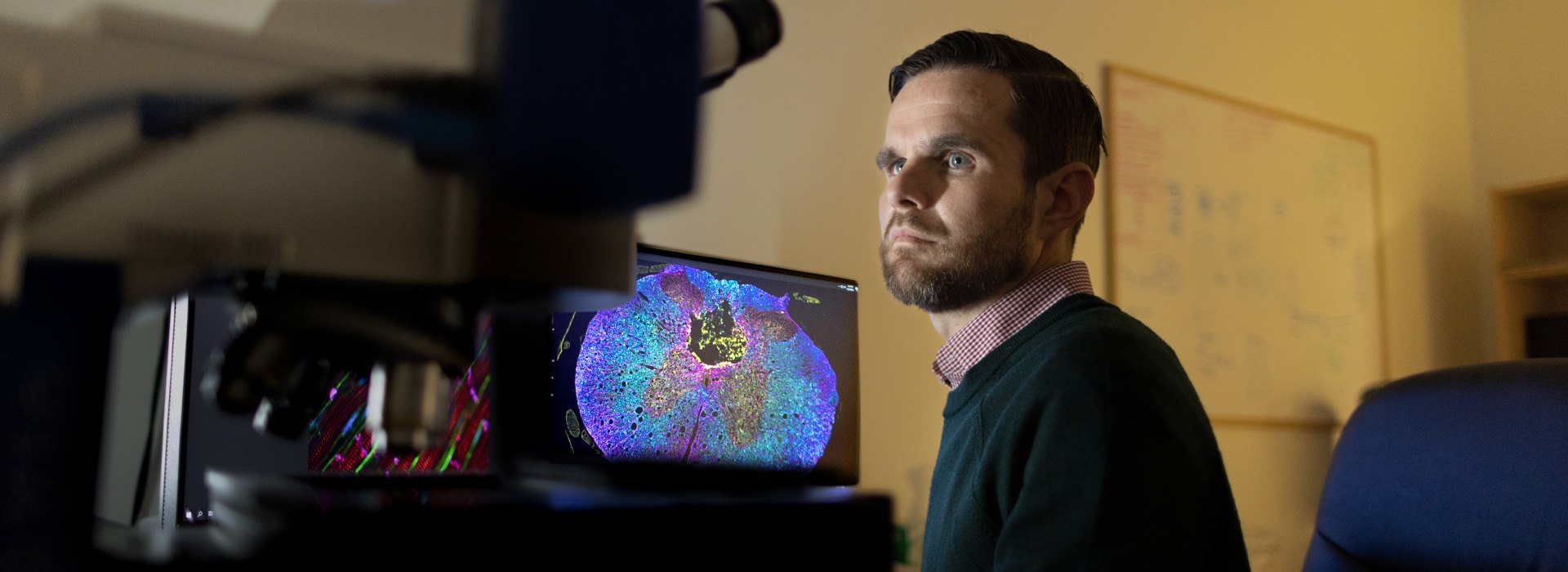

Dr. Christopher West and his team explore technologies to help people with spinal cord injury.

Every year, an estimated 4,500 Canadians suffer a life-altering spinal cord injury (SCI). The effects can be far-reaching, and not all of them are well understood.

While considerable global research has been focused on getting people with SCI to walk again, “comparatively little has been done to comprehensively understand what happens to the body’s systems that are under automatic control after a spinal cord injury,” says Dr. Christopher West, an associate professor and investigator with the Faculty of Medicine’s Centre for Chronic Disease Prevention and Management at UBC Okanagan (UBCO).

His research focuses on the impact of SCI on cardiovascular health.

“Cardiovascular disease… is the leading cause of death for people with spinal cord injury. That’s due in part to reduced brainstem control over the nerves that regulate blood pressure, blood volume and heart function. The question is, how can we help these people live better, longer, healthier lives?”

Dr. West, who is also a principal investigator with iCORD, first became involved in SCI research as a graduate student at Brunel University London, where he worked with the Great Britain Wheelchair Rugby squad.

“I thoroughly enjoyed working with this group and became intrigued by how SCI impacts pretty much every bodily system,” Dr. West says.

“That’s how I decided I wanted to continue my research in this area.”

Associate Professor and Investigator,

Centre for Chronic Disease Prevention and Management

In his work, Dr. West wants to know two key things: First, how can we better protect the spinal cord after immediate injury to preserve the nerves that ultimately control heart, lung and autonomic nervous function? Second, what kinds of interventions can be developed to offset long-term cardiovascular disease progression?

For the 85,000 people in Canada living with SCI — and the many more around the world — the answers to these questions could lead to better long-term health and longer lives.

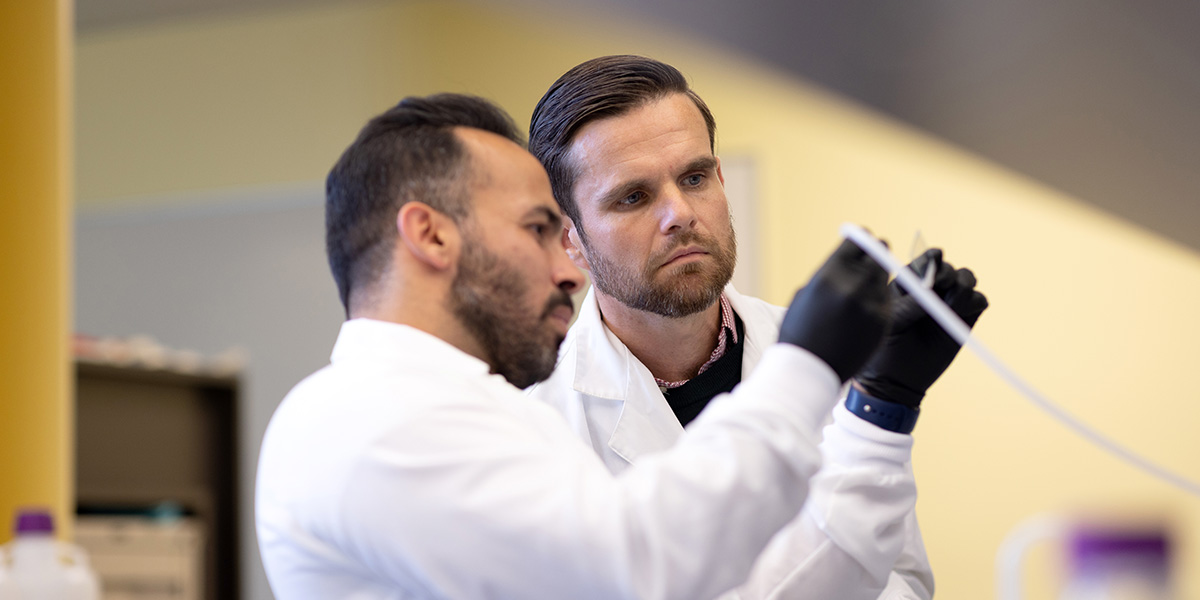

Dr. Christopher West (right) and his graduate student, Mehdi Ahmadian, are exploring how neuromodulatory treatments—or those that enhance or inhibit the transmission of nerve impulses— impact the cellular composition of the spinal cord and heart. This is important to understand the downstream impacts of a new therapy.

Experts from UBC a key part of international project

Dr. West is part of an international team of scientists from UBC/UBCO, the University of California-Davis, the University of Calgary, and a number of other institutions and biotech companies who, together, aim to revolutionize spinal cord research. Funded through a grant from the United States Defence Advanced Research Project Agency, the team is developing innovative, implantable stimulation technologies that target the spinal pathways responsible for controlling cardiovascular function.

“Our hypothesis is that by implanting a stimulator on the spinal cord, we can re-engage the systems that control cardiovascular function” explains Dr. West.

“The stimulator uses information from a sensor that measures blood pressure and a second sensor that measures oxygenation of the spinal cord. Our theory is that when blood pressure drops, the amount of stimulation will increase. This raises blood pressure, which in turn brings more blood flow and oxygen to the spinal cord.

“A lack of oxygen to the spinal cord is one of the biggest problems following injury, and low blood pressure is a major contributing factor to that.”

Dr. West adds that if oxygen can be delivered in a more efficient way to the spinal cord one-to-seven days post-injury, this can hopefully prevent — or delay — some of the secondary damage that happens after an SCI.

“Normal blood pressure, heart function, better respiratory function, movement sensation, bladder function, bowel function — all these things depend on nerves travelling down the spinal cord unimpeded,” he says.

Dr. West works closely with Dr. Brian Kwon, a UBC professor in the Department of Orthopaedics, the Canada Research Chair in Spinal Cord Injury, and the investigator leading the UBC team on the implant project. The team will develop the spinal cord sensors and test them on animal models; by 2025, UBC is anticipating to lead the first human implant at Vancouver General Hospital.

This aspect of the project brings together experts from UBC Vancouver and UBCO. Dr. West emphasizes the value of inter-campus collaboration.

“As the project progresses, having someone involved from B.C’s Interior will also help with disseminating information to the wider SCI community in the province,” he says.

“My greatest hope is that we can reduce the severity of spinal cord injuries and help people live stronger, healthier lives.”

Share this Story

This story was republished on February 13, 2023. The original version of the story is available on the UBCO News website.