Endometriosis remains largely understudied despite being a relatively common condition. Affecting about one in 10 women of reproductive age, its occurrence among the Canadian population is only slightly behind type 2 diabetes. Characterized by the growth of endometrial-like tissue outside the uterus, the condition is a leading cause of pain and infertility among women, and in Canada alone it is associated with more than a $1.8 billion annual financial burden and chronic health impacts.

Now, a new research project co-led by scientists at the UBC faculty of medicine has received a $2.2 million USD grant to examine the genetic drivers of endometriosis, with an aim toward improving diagnosis and accelerating the development of precision treatment strategies, particularly for diverse and underserved communities.

“The hope with this project is that eventually we can test for precision medicine therapeutics,” said Dr. Michael Anglesio, assistant professor in the department of obstetrics and gynaecology. “We want to learn if a patient has a certain genetic mutation, should they get a specific treatment to target that mutation. This is a first step, hopefully, of many steps towards getting better recognition for a complex disease.”

The five-year grant is being funded by the US Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development.

The project, led by Dr. Anglesio and Dr. Kate Lawrenson at Cedars Sinai Medical Centre in Los Angeles, is a first-of-its-kind look at the interaction between individual genetics and somatic genetics, which are non-heritable mutations that only affect diseased cells. The project aims to better understand the spectrum of genetic factors underpinning endometriosis, and how these factors differ across different racial groups, including White, Asian, Black and Hispanic women.

The grant follows a 2023 publication from UBC’s Dr. Anglesio and Dr. Paul Yong that suggests somatic “cancer-driver” mutations may be more prevalent in endometriosis lesions that affect non-white – predominantly Asian – individuals. Despite the ominous name lent to these mutations, endometriosis rarely develops into cancers.

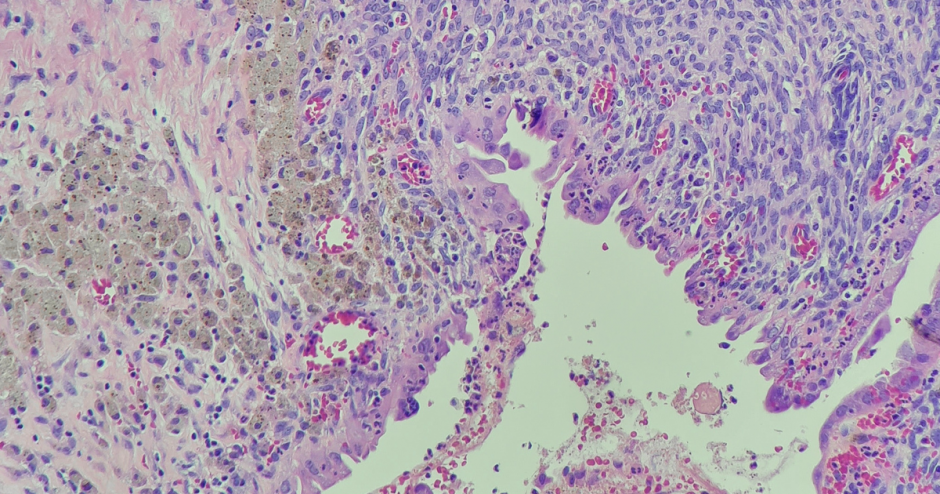

While endometriosis lesions can vary in size, the actual endometriosis cells in a lesion make up only a small part. The ability for researchers to study somatic mutations in specific endometriosis cells is relatively new since the required technology wasn’t available even a decade ago.

“The hope with this project is that eventually we can test for precision medicine therapeutics.”

Dr. Michael Anglesio

“We know a little about these mutations from our studies of cancer,” Dr. Anglesio says. “We think the mutations are helping endometriosis cells survive and move around in the body. Sorting out exactly how these mutations affect a condition that isn’t cancer is a new area of exploration, and almost every individual with endometriosis has a different experience.”

UBC researchers are using a combination of two methods to examine surgical specimens: ultra-high resolution mutation detection methods, a type of next-generation sequencing that is common in early-detection cancer research, and laser capture micro-dissection which is used to separate out the endometriosis cells.

The project will combine these technical methods with research from Dr. Lawrenson’s lab at Cedars Sinai and robust data collection from patients in Canada and the US. The UBC team also includes faculty of medicine researchers Dr. Yong, Dr. Aline Talhouk and Dr. Anna F. Lee who each contribute their unique specialized skills to the project, from pathology to risk modelling.

While Dr. Anglesio’s past research identified different types of endometriosis and varied mutations of the diseased cells, they haven’t yet found a correlation between symptoms or outcomes for treatments.

Now, boosted by new funding and collaborative, interdisciplinary efforts, this project aims to help address this gap and provide hope for women around the world.

Contributors to this study include Drs. Anna F. Lee, Aline Talhouk and Paul Yong in Vancouver and Drs. Kate Lawrenson, Fabiola Medeiros, Matthew Siedhoff, Mireille Truong and Kelly Wright in Los Angeles.