The Next Big Question Series

Can your breath be used to detect lung cancer?

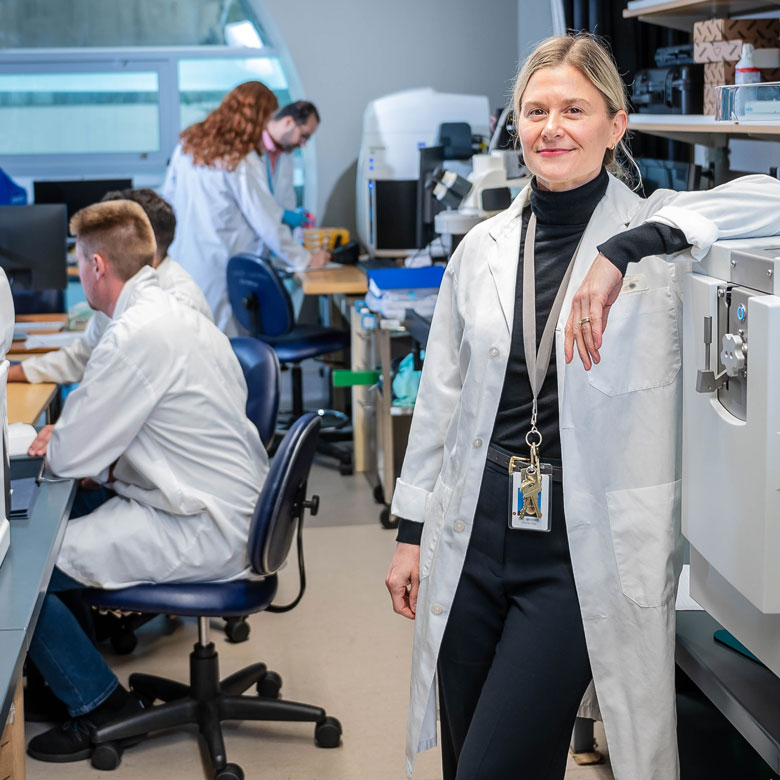

In the first laboratory of its kind in North America, UBC’s Dr. Renelle Myers is harnessing the power of breath in the hopes of saving more lives, sooner.

Killing more people every year than breast, colon and cervical cancer combined, lung cancer is the deadliest form of cancer globally.

Currently detected using an imaging test, such as a CT scan, lung cancer is typically confirmed by biopsy — whereby a sample of tissue or fluid from around a patient’s lungs is carefully extracted and examined under a microscope.

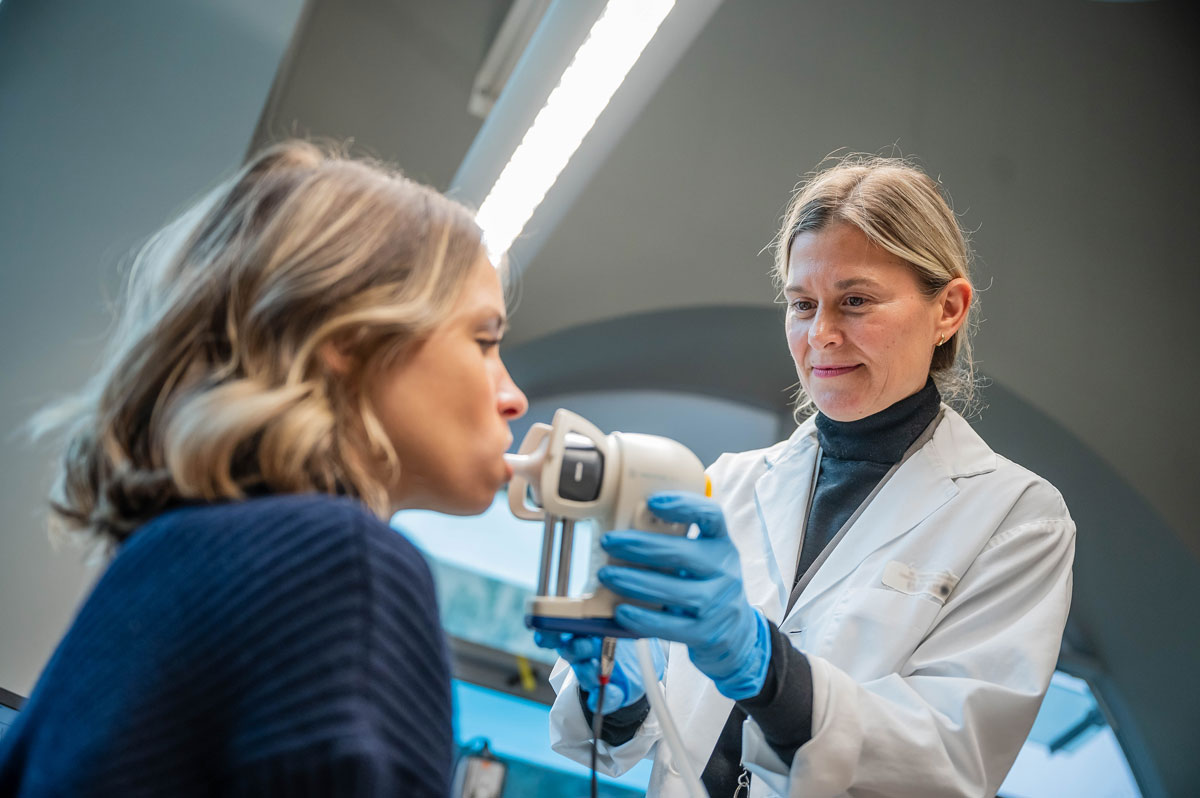

But what if the world’s deadliest cancer could be quickly and easily detected using something as simple, and painless as a breath test?

That’s the big question driving the work of Dr. Renelle Myers, a clinical associate professor in UBC’s department of medicine.

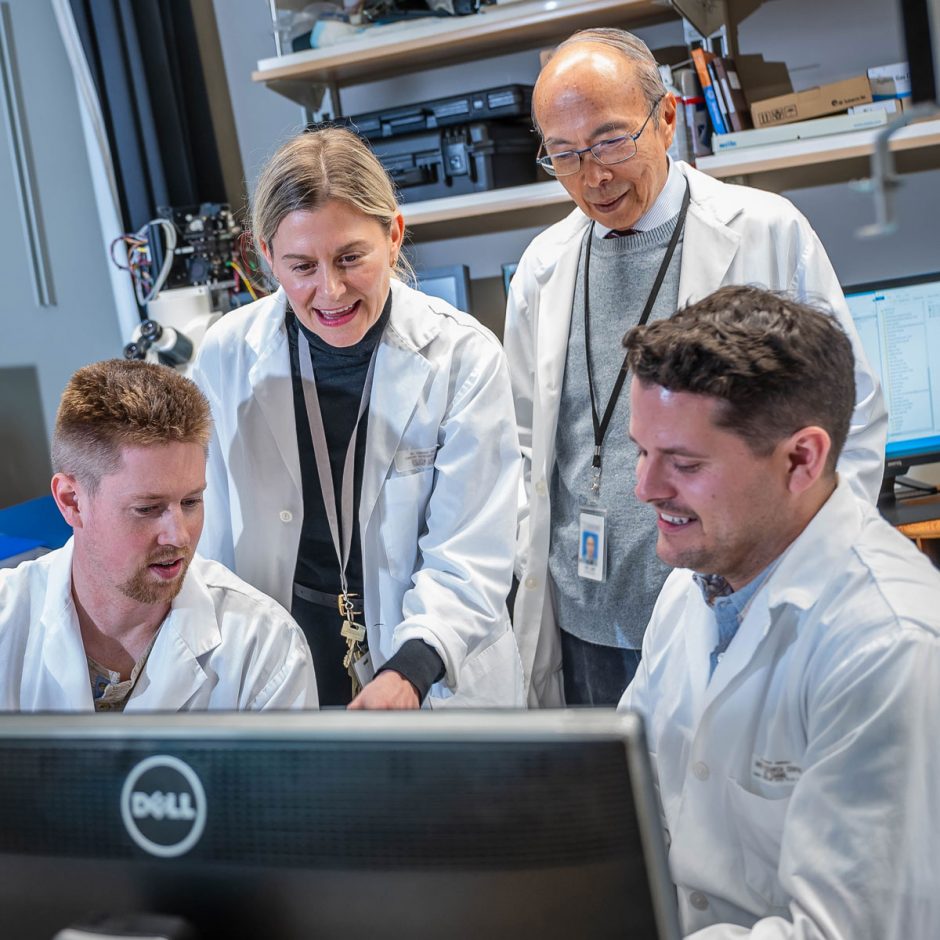

At the Breathomics Lab, housed at the BC Cancer Research Institute — a UBC Faculty of Medicine research institute — Dr. Myers leads a team of highly-trained chemists, researchers and UBC graduate and postdoctoral trainees to study hundreds of breath samples collected from patient participants.

Each day, they comb through thousands of organic compounds, looking for potential patterns or biomarkers that could one day be used to help signal the presence of lung cancer.

“I like to think that we’re searching for a fingerprint — a mark of what ‘is’ cancer, and what ‘is not,’” says Dr. Myers.

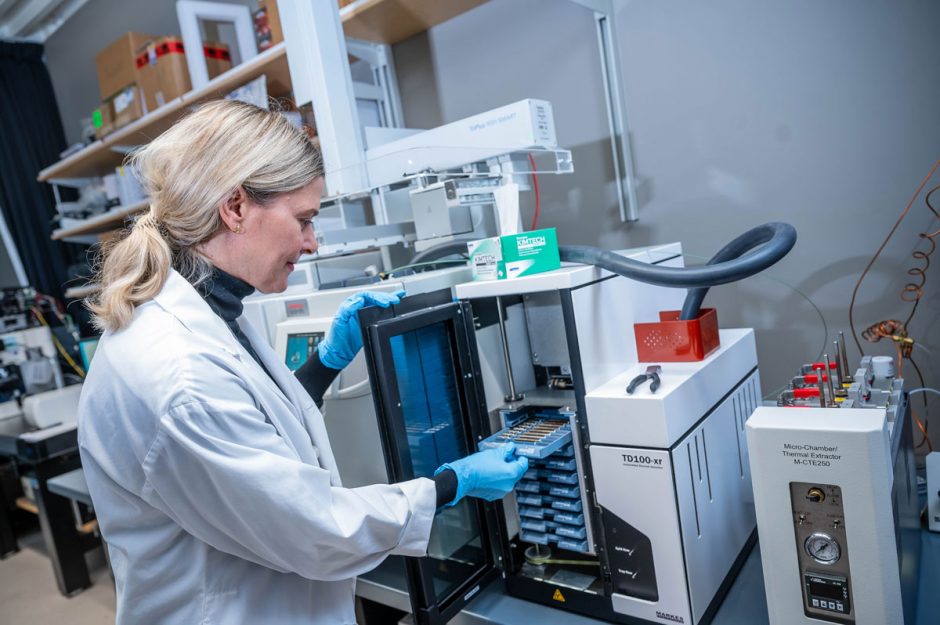

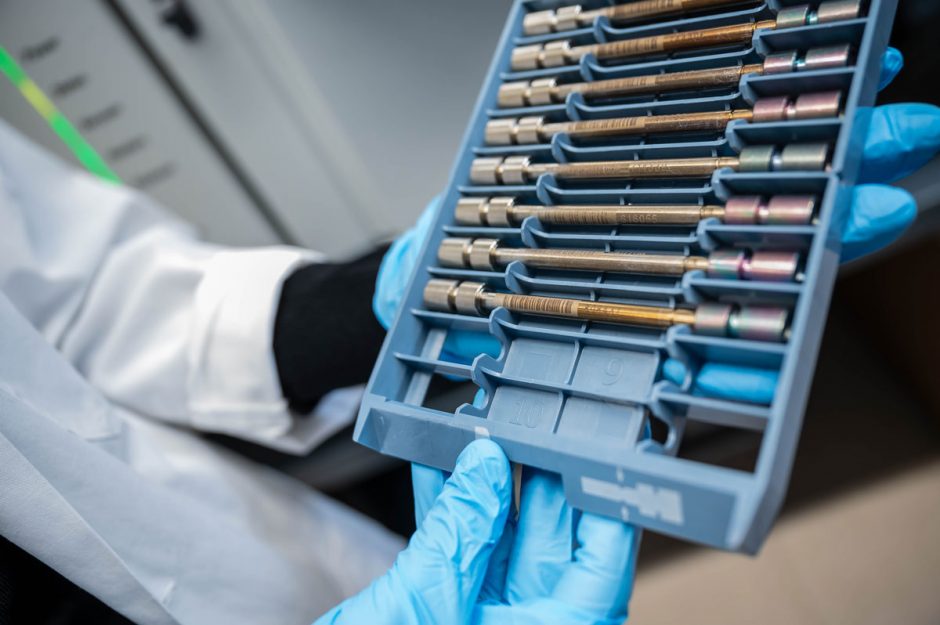

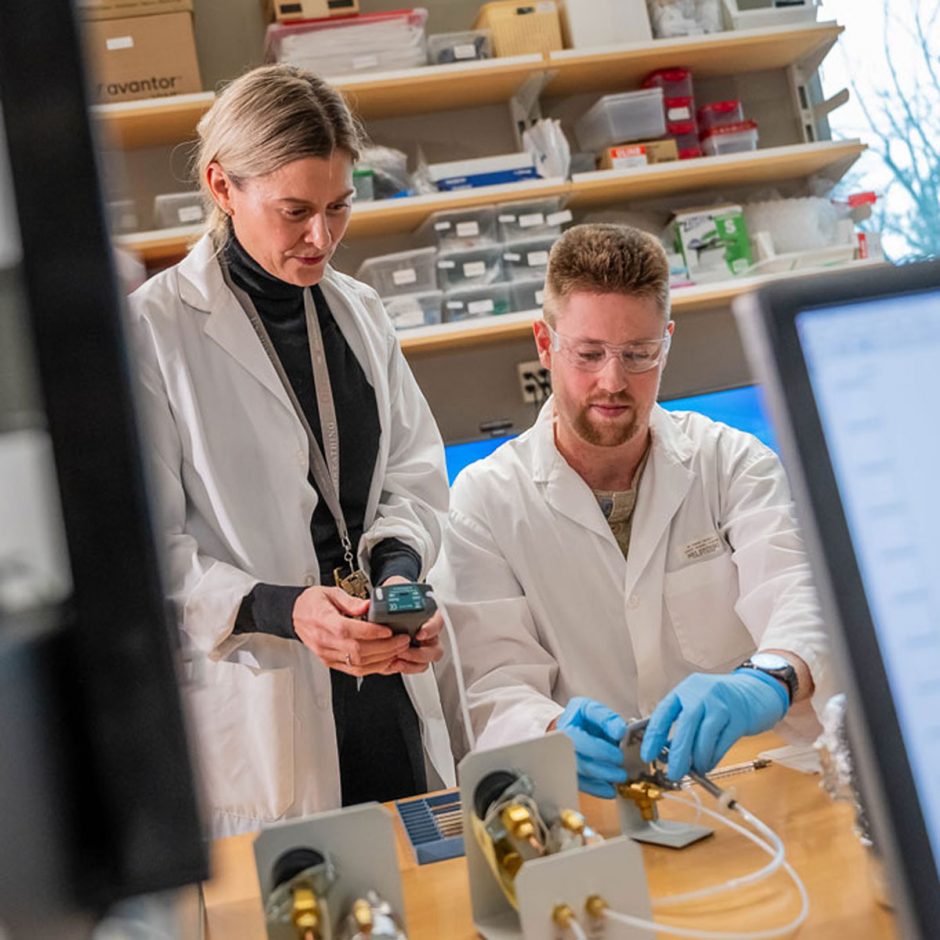

Dr. Renelle Myers removes a tray of tubes containing breath samples.

To conduct this cutting-edge research, her team uses a specialized collection system to gather breath samples from participants and capture it in small tubes. The tubes are then heated to nearly 150 degrees Celsius (or 300 degrees Fahrenheit) in a process known as thermodesorption.

In such extreme heat, the stored breath releases volatile organic compounds (VOCs), which are then run through gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) — it’s here where each compound is separated out and ultimately identified.

“With everything we do, we’re working to move the needle forward so that we can detect lung cancer earlier and save lives sooner.”

Dr. Renelle Myers

As the first clinical breath lab in North America, the work of Dr. Myers and her team comes at a critical time as clinicians are seeing a growing rate of lung cancer among patients without a history of traditional risk factors, such as tobacco use.

“We’re seeing more and more never smokers with lung cancer,” says Dr. Myers, who also works as an interventional respirologist at Vancouver General Hospital, where she regularly performs lung biopsies and supports patients on the receiving end of devastating diagnoses.

Dr. Renelle Myers collects a breath sample for further investigation.

Dr. Myers hopes her research will not only help to shed light on these rising rates of lung cancer, but make a critical difference in the lives of patients and their families.

“When detected early, lung cancer is curable — but, unfortunately, in the majority of cases, symptoms don’t typically appear until the cancer is already in an advanced stage,” she says.

Which is why regular screening has a huge role to play when it comes to increasing survival rates — helping detect cancer early, when treatment is most effective.

In the spring of 2022, thanks to the hard work of researchers, including Dr. Myers, and her colleague UBC’s Dr. Stephen Lam, a professor in the Faculty of Medicine’s department of medicine and distinguished scientist at BC Cancer, B.C. became the first in Canada to implement a provincial lung cancer screening program for those considered high-risk.

Inside the Breathomics Lab, Dr. Renelle Myers works alongside colleagues, including Dr. Stephen Lam (back right in last photo).

But, with a new breath test on the horizon, Dr. Myers hopes physicians will be able to one day diagnose and treat more patients (particularly those not traditionally considered high risk) even sooner — and not just patients here B.C., but those across Canada and around the world.

“If we can create a non-invasive breath test to quickly identify that a patient likely has lung cancer at the point of care, then I think we could have the largest impact on lung cancer there has ever been,” says Dr. Myers, who is hopeful that a breath test for lung cancer will be possible within five years.

“With everything we do, we’re working to move the needle forward so that we can detect lung cancer earlier and save lives sooner,” she says.

By the Numbers

- B.C. was the first province in Canada to implement a provincial lung cancer screening program.

- Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer-related death in B.C., across Canada and worldwide.

- Six British Columbians die of lung cancer every day.

The Next Big Question

Go behind the scenes with UBC Faculty of Medicine researchers who are sparking new ideas, asking big questions, and helping unlock remarkable discoveries to help transform health for everyone.

Published: February 12, 2024