Dr. Peter Jepson-Young (second from left) and Dr. Deborah Money, Executive Vice Dean for the UBC Faculty of Medicine, (second from right) celebrate their graduation from UBC medical school. (Courtesy Dr. Deborah Money)

“From the first day… I was determined to beat this thing.”

When Peter Jepson-Young was diagnosed with AIDS in 1986, he had just finished his medical training at UBC and was looking forward to starting his own practice. After experiencing several health complications, he shifted his focus dedicating his career to AIDS education and awareness.

Teaming up with CBC Television to create the Dr. Peter Diaries, Dr. Peter invited the world into his life – to experience the pain of cancer, going blind, and bouts of pneumonia, but to also revel in the joys of re-learning how to play the piano and downhill ski.

Through the creation of the Dr. Peter AIDS Foundation and the Dr. Peter Centre, the late Dr. Peter continues to inspire patients, advocates, researchers and health professionals around the world to improve care and treatment for people living with the disease.

His close friend and former medical school classmate Dr. Deborah Money, Executive Vice Dean for the UBC Faculty of Medicine, says people gravitated toward the energetic and charismatic man who would later become the subject of an Academy Award-nominated documentary.

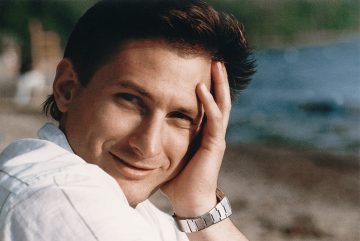

Dr. Peter Jepson-Young (Courtesy Dr. Peter AIDS Foundation)

We spoke with Dr. Money to learn about Dr. Peter’s legacy and how he inspired her work.

How would you describe Dr. Peter?

He was warm, fun-loving, a great friend and devoted to his family. He was very dedicated to medicine, but also not the most bookish in the class. He didn’t always go to lectures because he knew I did and always took notes – because I’m one of those – and Peter would go to the gym instead (he was always very athletic and fit) and then say, “Do you mind if I borrow your notes!”

What is the impact of his legacy?

When Peter appeared on primetime CBC newscasts after his diagnosis he really helped break down the stigma associated with AIDS, bringing the conversation of HIV into the living room by huge numbers, here in B.C. and across the country.

He knew how fortunate he was to have had family and friends rally around him, and he realized that was not the case for a lot of people. Many others living with HIV were either shunned or disowned by their families, and dying in hospital beds alone. It’s why he started the Foundation and the idea of comfort care.

How has he inspired your work?

I was very motivated to understand this disease after I watched Peter with it.

I’ve been in prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV for my entire career and I continue to lead that program in British Columbia. The Oak Tree Clinic is a women and family centred HIV clinic, where we see women – including pregnant women – living with HIV/AIDS and HIV-infected and exposed children. One of our significant research programs in HIV — primarily from a women’s perspective — looks at how to prevent transmission and then how to make sure that the drugs we used were safe on pregnancy. We’ve also been researching the prevention of cervical cancer in women living with HIV.

We’ve come so far in terms of HIV/AIDS research and treatment. What new developments do you see happening in the near future?

Dr. Deborah Money, Executive Vice Dean for the UBC Faculty of Medicine

The good news is we have effective treatments that suppress HIV and can give you almost a normal lifespan. There are minimal side effects from the medication and your risk of transmitting to others is nearly zero. The bad news is you have this disease for life. We have drugs that make a huge difference, but require daily medications. To date, the development of a vaccine and curative therapies have still eluded us.

There’s also the societal reality. Much of this disease globally is in low and middle-income countries where medical care infrastructure and social determinants of health are such a huge challenge. We must solve some of the social and global issues that allow this disease to disproportionately affect people living in poverty, and people who don’t have access to health care and prevention.

Where do we go from here with HIV/AIDS awareness?

Although there’s been extraordinary achievements in treatment, this disease hasn’t gone away. The need to study and understand it hasn’t gone away, and the need to understand that people with this disease are just people and shouldn’t be shunned is still hugely important. People with HIV are still fearful to tell others. If you get diagnosed with breast cancer – everybody rallies. If you get diagnosed with HIV, friends and family often are not so supportive. For people with new diagnoses I still have to say, “It’s okay to just live with people, and eat with them, and share food and hug them and kiss the kids. It’s okay.”

Battling for a cure, vaccines and distribution of health care to low and middle-income countries are big tasks, but stigma we can tackle starting today, that’s within our grasp. It would be lovely if there wasn’t one person with this diagnosis that had to hide it.

In 2017 there were 36.9 million adults living with HIV and 1.8 million people newly infected with HIV, of which 180,000 were children. There are approximately 75,500 people living with HIV in Canada and more than 2,000 new HIV infections each year.